When I was in college, much of the physics curriculum didn’t quite take for me. As I got later in my academic career, some of the ideas started to make more sense. Now, many years later, I have been seeking to relearn some of the material. To be honest, some of that relearning is probably learning things for the first time that I didn’t really learn when I had the class.

I greatly admire Feynman’s lecture style and the way he weaves insights into his lectures. While I do not claim that I always absorb the insights or that I have yet internalized all the material from his lectures, I am working on it. In Feynman’s preface to his printed lectures, he talks about his opinion that there has to be a direct relationship with the student where the student thinks about the ideas, asks questions, and discusses the ideas. When I read that the first time, that idea did not particularly strike me. It means more to me years later after reflecting on it terms of my own lived experience and a quote from the Hagakure. While I know that Feynman enjoyed his time in Japan, I have no idea if he read or agreed with any of the ideas in the Hagakure. But, this quote from the Hagakure “To give a person an opinion one must first judge well whether that person is of the disposition to receive it or not” seems to have a lot of similar wisdom on how and when to communicate as Feynman’s idea on how best to teach.

Over the years, I have come to recognize that it is difficult for me to differentiate between what I want to talk about or what I think is interesting and what others want or need to hear. That is true for me at work, at home, and outside of work. I was reminded of that in a humorous way just this week. At a dinner with work friends and colleagues, one of my companions asked a physics question that their son wanted asked. “If an astronaut farts in space, does that make them move?”

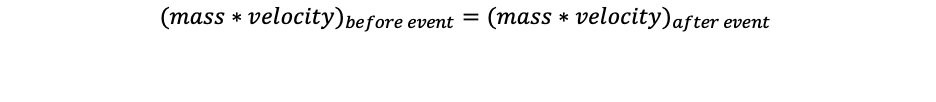

I don’t know if there is as much information about the universe and how it works in the answer to that question as there is in Feynman’s atomic hypothesis, but there is a great deal of information to sort through in order to answer the question. The simplest answer to the question is “yes.” The physics involved is the same as what makes a rocket move forward. It is conservation of momentum. Rockets work by expelling gas. Between two instances, linear (in a straight line) momentum is conserved.

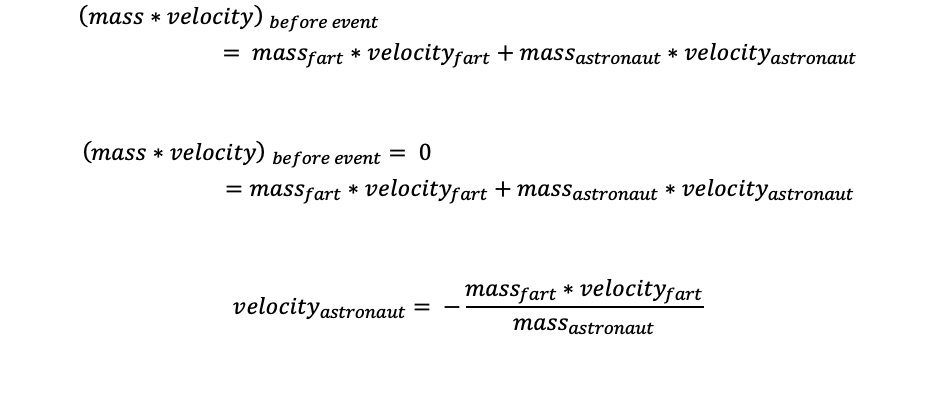

In my own thinking about the complications of this, I realized that this simple example also involved the complexity of what is involved in defining the system. Simply put, what is the mass and what is the velocity at each instant? For our humorous example, before the “event” the astronaut and the fart are one. Their combined velocity is zero. After the “event,” the equation on the right hand side of the first equation is really:

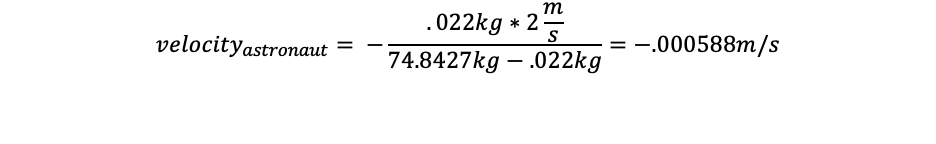

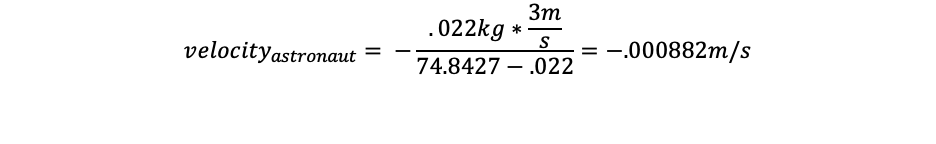

There is a bit of a complexity in that we will have to be careful to keep track of the mass of the fart. For this humorous example, the numbers from a quick internet search are likely to be good enough. If a typical astronaut weighs 165 lbs, that is equivalent to 74.8427 kilograms (I use SI units because it is harder for me to mess up the units). While 74.8427 may seem like an unnecessarily precise number, the astronaut is so big relative to the size of a fart that it is important to wait until the end to round. Based on a quick internet search, a typical fart can be estimated to have a mass of 22 grams or .022 kilograms. Similarly, the internet gives values of 2-3 meters per second for the velocity of a fart. Based on some quick algrebra, we can rearrange our equation to find the term we want:

Remembering that we have to be careful about the mass of the fart and the mass of the astronaut, we have

or

Those units don’t look big, but while I like calculating in SI units, my intuition for what quantities mean is entirely based on English units. So, I have to convert these numbers into something that makes sense to me. After the “event,” the astronaut would be propelled at something like 0.00132 miles per hour to 0.00197 miles per hour in opposite direction that they farted. If there were no more “events,” after a day, they would have drifted 167-250 feet as result of this propulsive event. So, while it is a small force, it is real.

In terms of the Hagakure, this simple but humorous example has helped me better realize that recognizing what people are ready to hear and the terms in which that they can hear it makes a huge difference to whether or not people can hear what you are saying. Whereas impacting billiard balls may be a fantastic example to use with some people to explain physics, in this case farting astronauts seems to have been a much more effective example. And, in the end, the goal is to communicate, not just to say what I might want to say. While I am not going to claim that I am always great at differentiating between what I want to talk about and what others might to talk about, this particular vignette is helping me think about it. My personal takeaway from thinking about the life lessons from this humorous physics example is that the most important part is the connection and not the content.

Leave a comment