Real systems are messy, noisy, difficult to measure, and can be a challenge to control. Organizations and organizational dynamics often exhibit analogous behavior.

In control systems, it is common to analyze linear single input single output systems. There is a lot that can be done with those tools. However, applying these tools comes with accepting some compromises. Addressing complexity and improving performance comes with cost and complexity of a different form. In real systems, noise matters, nonlinearities and interactions are unavoidable, there are errors in measurements, and nothing behaves in an ideal manner. In my experience the same is true in organizations.

I will use the inverted pendulum as an example and as an analog.

Figure 1: Inverted Pendulum Diagram

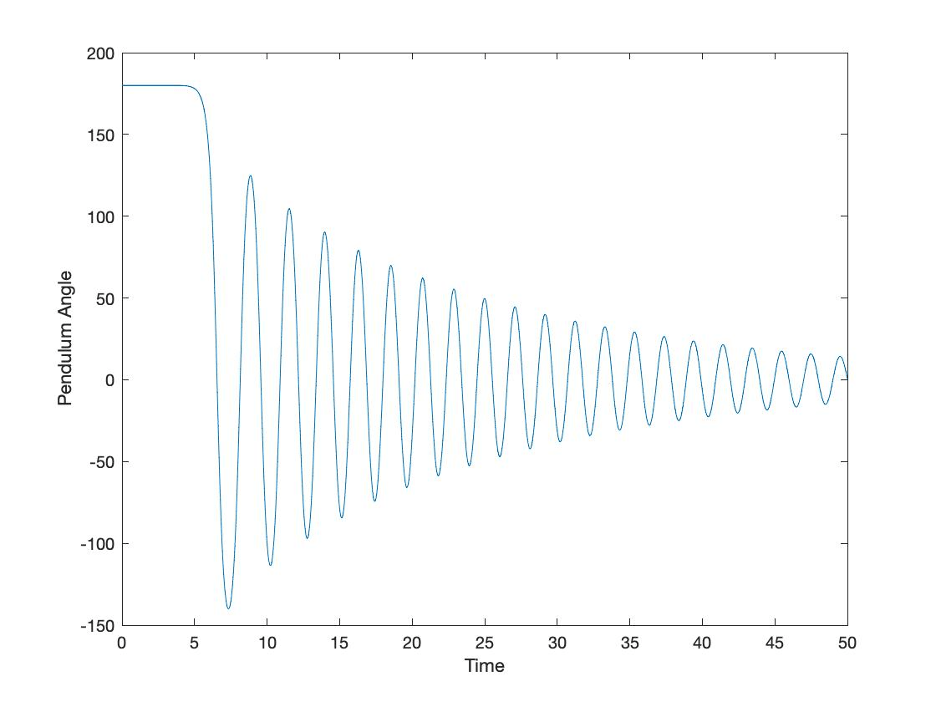

To start, I will assume that cart is fixed in place and that the only thing that can move is the pendulum. At the beginning, the pendulum is perfectly upright. Intuitively, we know that bumping into the system will cause the pendulum to tip over. If we model that scenario, assuming that the angle of the pendulum is 180o when it is directly over the cart and 0o when it hanging below the cart, the angle of the pendulum looks like this after it gets nudged.

Figure 2: Inverted Pendulum Response to a “Nudge”

Just like with management forecasts and decision models, a great number of assumptions and idealizations are embedded in this simple plot. Like all real systems, this simple model assumed that some damping or friction would be present. For this simple simulation, the value plotted is the actual estimated physical value, not what a real signal measured with signal noise and signal error might look like. But like a previous post discussed, we are computing for insight.

What we learn from this plot is that a small nudge, any nudge in fact, will cause the pendulum to tip over. Like we expect, we also see that it converges towards a condition where the pendulum settles out with the pendulum hanging below the cart. It doesn’t ever go back to where it is standing up straight in a balanced way. That is an unstable state and we have to do something to control it in that state.

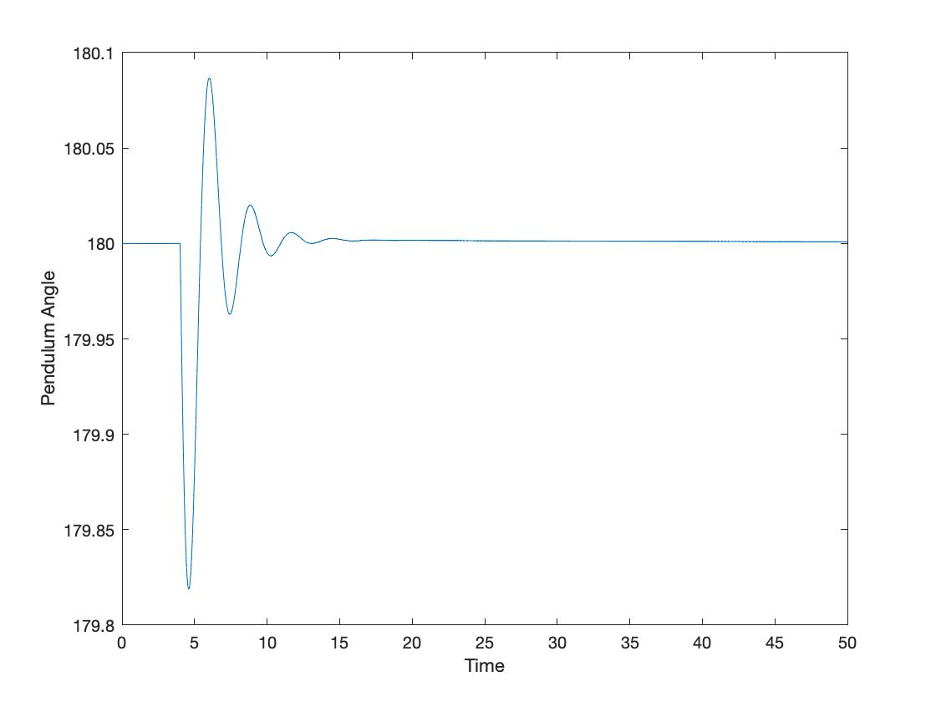

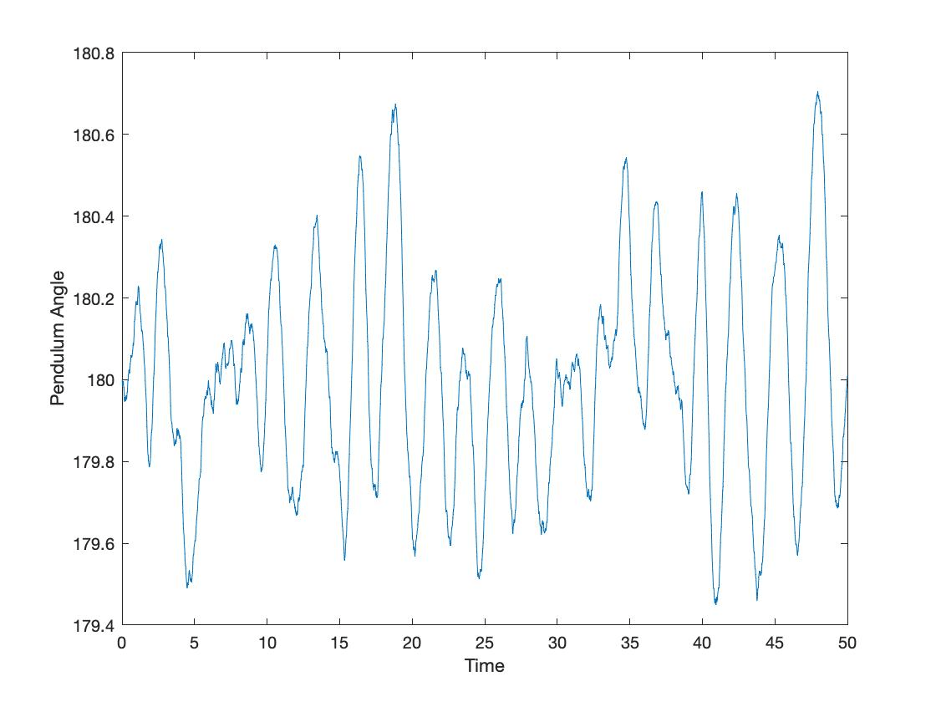

If we add what is called a PID controller, which generates a force that depends on how far the pendulum is from its desired state, how fast it is moving from its desired state, and the total error from its desired state over time, we can get a response that looks like the following plot.

Figure 3: Inverted Pendulum Response to a Nudge with a Stabilizing Controller

The big difference in this plot is that all the movement is really small deviations around the straight up and down location. In our management analog, this response is analogous to a finally tuned and very effective management system that is providing a near-perfect amount of management input to a team.

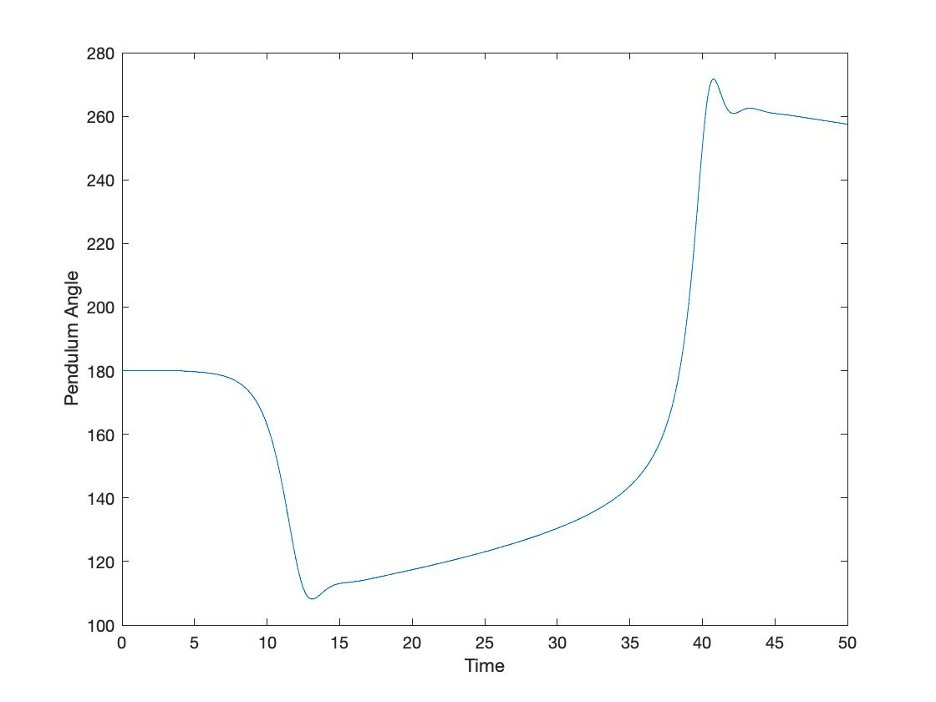

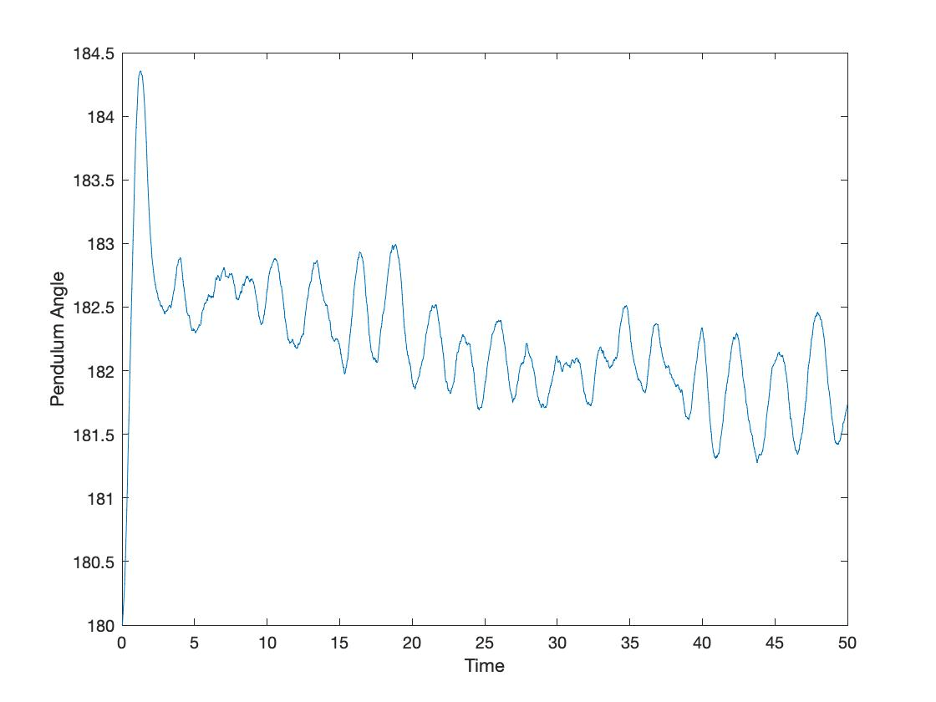

The next plot shows the same control structure and the same pendulum, but with much less forceful and energetic control.

Figure 4: Response of an Inverted Pendulum with a much “weaker” control system

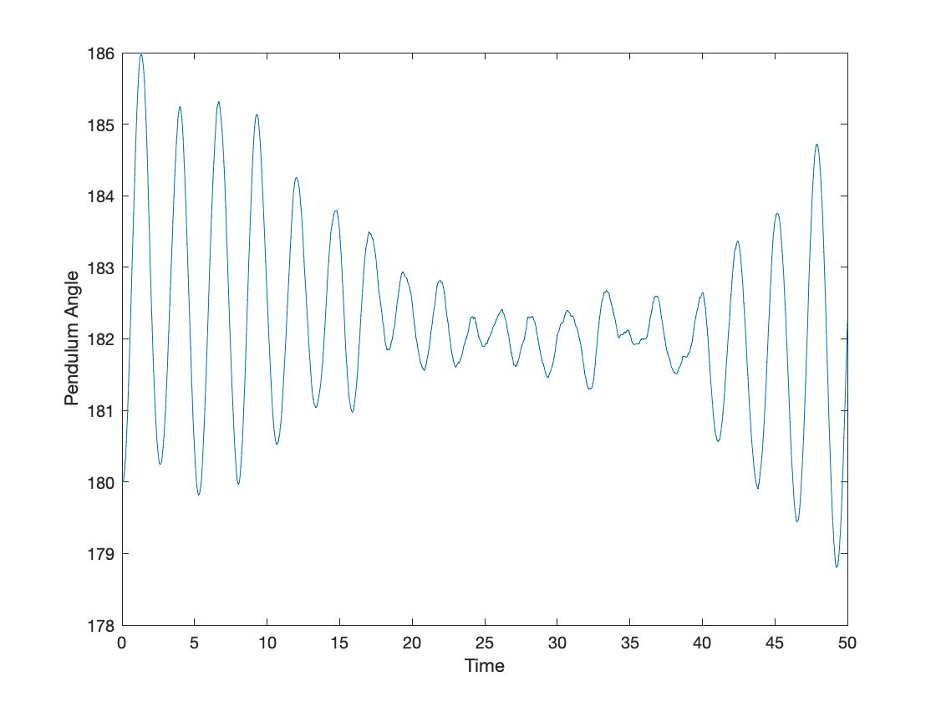

In this case, the control (or the management response) isn’t enough to stabilize the system. It isn’t the structure or the nature of the control or the management system. It just simply isn’t enough. There are other situations where the structure or nature of the control or management system is a poor fit for a situation, but that isn’t the case here. What about the other side of the coin? The next plot shows how the system responds to a MUCH more forceful management control system.

Figure 5: Response of an inverted pendulum with an over-powered control system

In this plot, note the scale on the vertical axis. This is an enormous number. In this case, too much gain has caused the system to become even more unstable. Over-management has made things worse than they would have been with no control system.

This simple control example shows a physical analogy to the idea that “enough management is good. Too much management or too little management is bad.”

While we are computing for insight, we can also explore the effects of noise on control system behavior (and by extension the effectiveness of management systems).

Figure 6: Example of the effects of noise

In this case, the control system is able to deal with the amount of noise that it is faced with in this scenario. An interesting dynamic is that this bit of mathematical exploration assumed that the noise was random. Sometimes the noise was positive. Sometimes the noise was negative. Sometimes, in physical systems the noise can be biased one way or the other. And, many organizations experience the situation where information gets “massaged” to be more positive as it flows up through an organization’s decision process. The next plot shows a simple example of how one-sided noise looks different than truly random noise.

Figure 7: Example of the effects of bias in noise

In this case, the bias in the noise causes a shift that the control system isn’t fully able to address. The control system doesn’t go unstable, but it can’t get back to the target state. If we add a bit more realism to the control system (and the management analog), we can incorporate the effect of some delays in measuring the location of the pendulum.

Figure 8: Example of the effect of measurement delays

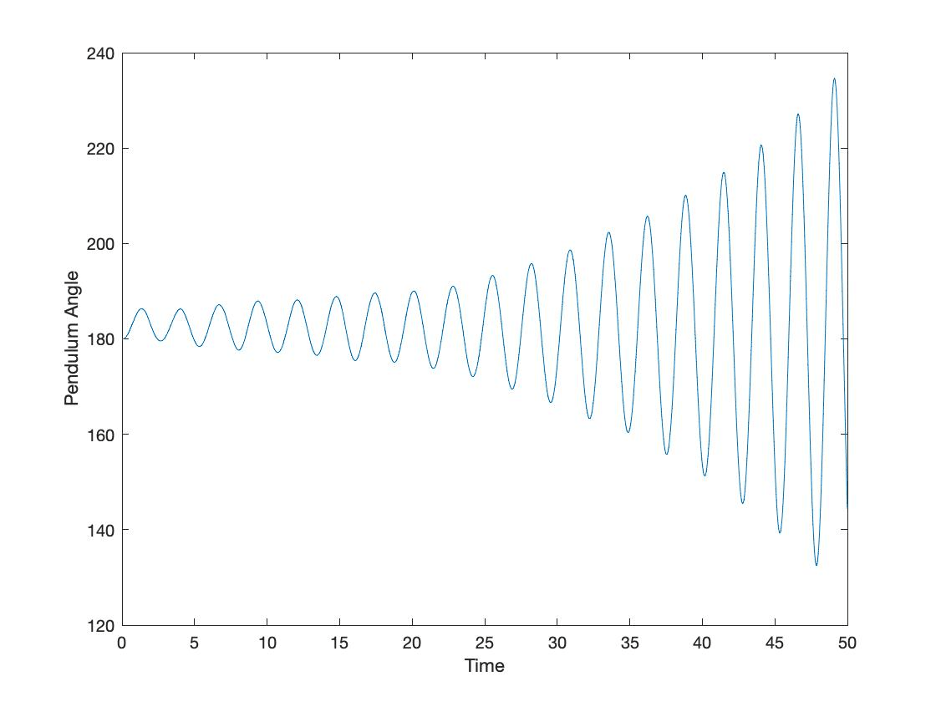

The plot shows that delays in measuring what is going on with the pendulum make the same control system less effective. This is unavoidable reality in any real system. In management systems, lags in information flows lead to lags in decisions which make the responses less effective. To extend the analogy a bit further, the next plot simulates a delay in applying a control response.

Figure 9: Example of the effect of delays in applying corrective action

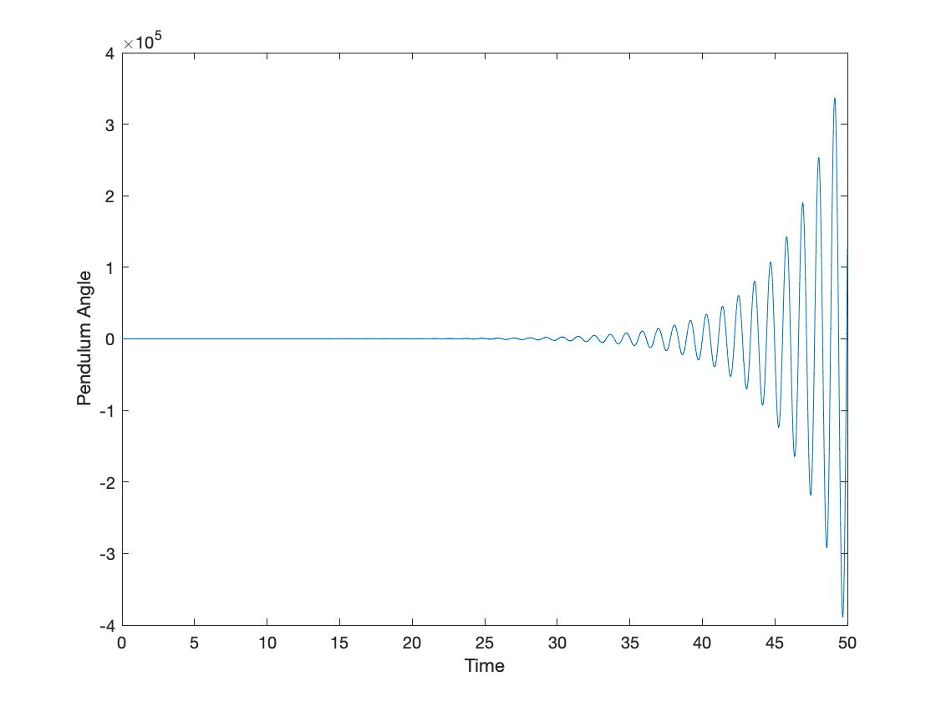

This plot shows the compounding effect of a delay in applying the needed corrective force. Just like in management systems, noise, plus lags in measuring the right information, compounded with delays in applying the needed management effort have taken what was a stable system in an ideal situation to an unstable situation in the “real world.” Sometimes, managers and management systems work on improving the accuracy of information acted on, reducing the delays in getting accurate information to decision makers, and acting in a timely manner. Sometimes managers and management systems try to make things better by doing the same things but doing them louder and more forcefully. The next plot shows what happens if twice as much force is used to respond as was used in the previous plot.

Figure 10: Effect of applying excessive force to respond to delays

As this plot shows, simply hitting the same system with more force in the same way without addressing the information accuracy, the timeliness of information flows, or the timeliness of corrective action did not make things better. In fact, this made things much, much worse.

In control systems and in organizational control systems, timely information flow, accurate information, appropriate responses, and timely responses make the difference between realizing the desired outcome and making things worse.

In a future post, I will extend this idea and this analogy to more complex dynamics and more complicated responses.

Leave a comment